By Raymond Lam | Buddhistdoor Global | 2021-02-01

Direct Link to Article

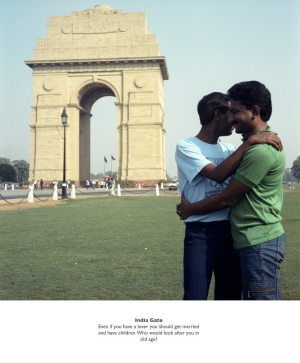

Driftwood (Heart Sutra). Tsai, Charwei. 2019.

Photo by Laura Gildner

Haema Sivanesan is a curator at the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria (AGGV), British Columbia. She has held leadership and curatorial positions in public galleries and visual art centers across Canada, as well as in Australia and South Asia. Her curatorial work typically focuses on art from South and Southeast Asia and its diasporas, with an interest in non-Western post-colonial and trans-national histories, world views, and practices. Recent exhibitions include: Imagining Fusang: Exploring Chinese and Indigenous Encounters (2019), Fiona Tan: Ascent (2019), and Supernatural: Art, Technology and the Forest (2018).

In 2018, Sivanesan was a recipient of an Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, New York, Curatorial Research Fellowship (2018–19); and in 2016, she was a recipient of a Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation, Hong Kong, multi-year research and exhibition development grant for the project In the Present Moment: Buddhism, Contemporary Art and Social Practice (forthcoming).

Buddhistdoor Global: How did you first become interested in the intersection between religion and art, and how did you find yourself working on spiritual themes in the secular context of a place like AGGV?

Haema Sivanesan: My background is in Asian art history, which requires a solid understanding of Asian religions, since a great deal of historical Asian art was commissioned for religious purposes. Prior to working at the AGGV, I had worked on a number of exhibition projects related to art and Buddhism. As a curator at the Art Gallery of New South Wales [Sydney, Australia] I worked on the major exhibition Buddha: Radiant Awakening, which opened in 2002. A few years later, I commissioned and curated a project titled دل كه سوز نوز ندارد, دل نيست (the heart that has no love/pain/generosity is not a heart), by artists Jayce Salloum [Canada] and Khadim Ali [Afghanistan/Pakistan/Australia], which opened at the Royal Ontario Museum [Toronto, Canada] in 2010 and subsequently toured internationally. This project looked at the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas in Afghanistan by the Taliban in March 2001. The project considered the impact of this horrific event on the local Shia Muslim Hazara community, exploring how these monumental images shaped the distinctive Hazara identity.

With my current project, In the Present Moment: Buddhism Contemporary Art and Social Practice, I’ve found myself working on Buddhism in the context of contemporary art because I wanted to examine the impact of Asian ideas in the contemporary West; and also find a way to think about Asian cultures outside of the limiting frame of “geographic” art histories. The tendency to historicize and orientalize Asia and Asian cultures in Western museums can limit how we understand Asian cultures as vital social and political forces in the contemporary world. In my work, I have become interested in finding ways to explore this, to address a long history of Asian-North American cross-cultural encounter, and to update how we understand the concept of Asia.

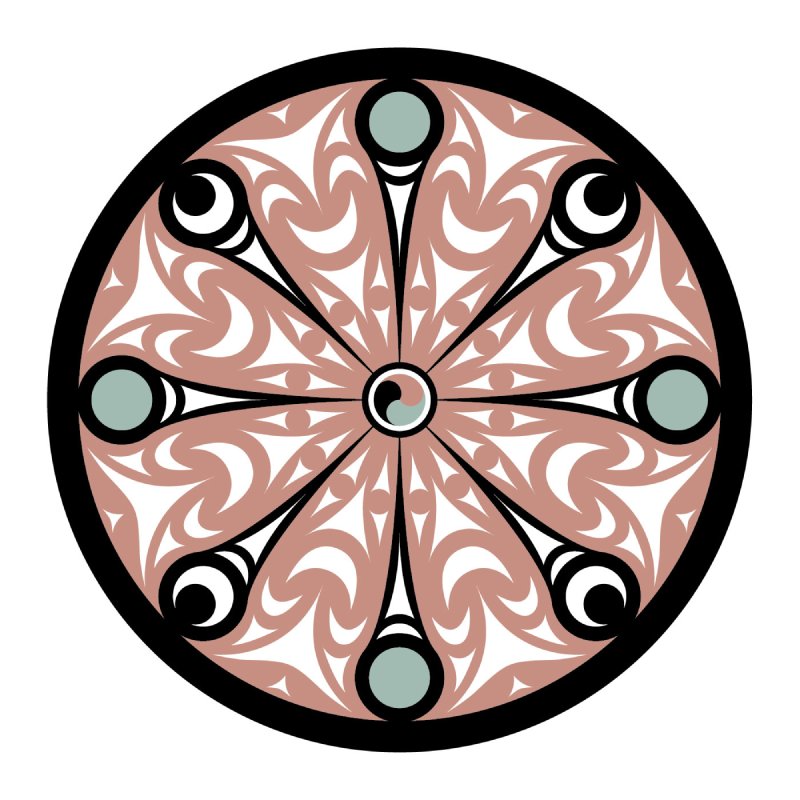

Rose Mirror Mandala, Stathacos, Chrysanne. 2013. Photo by Matthias Herrmann

Rose Mirror Mandala, Stathacos, Chrysanne. 2013. Photo by Matthias Herrmann

BDG: Any discussion would feel perhaps a bit out of touch without addressing the impact of COVID-19 on the art world. While the AGGV held a research convening from 25–27 October 2019, the exhibition’s exact date is not as certain as the upcoming book that you’re writing and editing. As a gallery curator and researcher, do you foresee any changes to the delivery of exhibits as they’re currently structured, or will things proceed as they used to with minor adjustments such as the compulsory use of face masks?

HS: The AGGV re-opened to the public relatively early, in May 2020, with strict COVID-19 safety protocols, and exhibitions drawn from the gallery’s permanent collection. But that said, there is a lot of uncertainty, especially for a project like this, which firstly requires the loan of art works from collections in the US, and which, secondly, looks at ideas of “social practice” in contemporary art. At this point in time, Canada’s border with the US remains closed; and social practice, which refers to collaborative or participatory forms of art, proves difficult given COVID-19. I have been using this lockdown period to revise and find ways to adapt some artists’ projects with relation to this exhibition, but the rest will need to be worked out once we know the state of things post-COVID. In the meantime, I have been focusing on a book that will accompany the exhibition. I’m very excited about the potential of the book, and the writers that I have been able to commission, including scholars, cultural theorists, and artists.

Learning Diamond Sutra. Zheng, Michael. 2013.

Photo by Julia Baier

BDG: You’re presently working on your curatorial thesis for the exhibition, which uncovers a long history of Buddhist influence in contemporary art in North America. Sutras such as the Avatamsaka, Vimalakirti Nirdesha, and the Diamond Sutra influenced several well-known artists in the West. Can you give a few of your favourite examples?

My research for this project has been very exciting, examining how Buddhism comprises a methodology of art practice. I have been very interested to understand how artists draw on their various art forms to explore Buddhist ideas—as a form of inquiry into various Buddhist concepts and teachings. These artists are not looking for ways to “illustrate” Buddhist teachings, but rather they use their art practice as a site where they can test ideas and verify their truth. So, artists’ expressions of Buddhist ideas are often quite personal, idiosyncratic, and perhaps misunderstood. In other words, the Buddhist underpinnings have been overlooked in mainstream discussions about their work.

For example, the well known American experimental composer John Cage created his famous work 4’ 33” (1952) as a response to his study of the Avatamsaka Sutra, and the American art critic and writer, Kay Larson has written extensively on this in a book titled, Where the Heart Beats (The Penguin Press 2012), which provides an important perspective toward the understanding of this work. Or Yoko Ono’s well-known performance artwork called Cut Piece (1966), which drew on the Jataka story of the Hungry Tigress, illustrated at one of the shrines at the temple of Horyu-ji, [Nara, Japan] to express ideas of selflessness and pacifism. Or the Taiwan-based artist Charwei Tsai, who has spent 15 years making work concerned with the Heart Sutra with great international success. Or the Chinese-born, San Francisco-based artist Michael Zheng, who has been making work that is deeply informed by his mother’s practice of the southern tradition of Buddhism in China, and his own practice of a more syncretic, modern Buddhism. The Diamond Sutra and the Platform Sutra have been important in his work. Zheng has commented:

My first exposure to Buddhism was when I was very little, when my mother “found” a master for me. I didn’t know what that meant. The only thing she said was, “I found a master for you. He said you had 慧根 (Buddha-nature).” But I didn’t really understand and perhaps didn’t care. So I had no actual relationship with my master until after I came to the United States, and even then, the only connection that I had with him was when I sent money to him, because my mother told me to. That was very early on, and I had no real understanding of Buddhism at all. Now I can kinda [sic] guess what that was all about. It probably had to do with accumulating merit via giving. My own contact with Buddhism was more intellectual. It was actually after I became an artist, and it was almost contrary to how my mother practiced her Buddhism, which was more as a religion. For me, I came to Buddhism through scriptures like the Diamond Sutra and the Platform Sutra. And they remain two of the most important writings in my life. I keep going back to them because I always feel like I don’t really get it. Maybe it is because they have this expansive wisdom that encompasses a lot of things. My actual practice comes through Westernized versions of Buddhism, including yoga, meditation, and so on. These are the practices that I do daily. Buddhism came into my art through these practices of yoga and meditation and rumination on the scriptures. (Ch’an Buddhism, being the confluence of the Buddhism from India and the various traditions rooted in Chinese culture such as Taoism, influences me most directly.) So, the way it manifests in my art tends to have a meditative quality, and I try to consciously incorporate the form of meditation in my art.

There are so many examples, even concerning art works that are very well known. Bringing an Asian cultural and theoretical perspective to the consideration of these works is important in order to have a more complete understanding of what some of these works are about.

Learning Diamond Sutra. Zheng, Michael. 2013.

Photo by Julia Baier

BDG: These artists work with Buddhist philosophy and concepts such as interdependence, causality, and oneness seem to blend with preoccupations of the Canadian experience, from colonization, immigration, and multiculturalism and First Nations life. What can Buddhist ideas contribute to the experience of Canadian statehood, culture, and literature?

HS: Unlike the US, Canada is a very secular society, and perhaps even a little nervous or anxious about spiritual, let alone religious, ideas having a place in contemporary art. So I am not sure that I have an easy answer to your question!

The AGGV hosted an artist-centred research convening in October 2019 to better understand artistic positions around some of these issues, and to consider why Buddhism has such a persistent influence in the practice of art. The responses and discussions were insightful and diverse. For example, the Toronto-based artist Chrysanne Stathacos talks about her introduction to Buddhism as coinciding with the death of her friends to AIDS in the 1990s, and how the Buddhist concept of impermanence gave her an important perspective. She reflects:

Looking back at my art practice . . . all the projects interlock with Buddhism, but it’s all based on the notion of understanding impermanence and understanding the feminine in Buddhism . . . it’s important to note that Buddhism came to me through a woman teacher. Not that I haven’t attended teachings by His Holiness, and not that I haven’t had male teachers, but I came to it from Jetsunma [Tenzin Palmo]. And that is also connected to my practice as an artist—being a feminist, and the exploration of the feminine through the work . . .

Or in another instance, the West Coast Indigenous (Coast Salish) artist, Qwul’thilum Dylan Thomas, says:

I started meditating, at first just for the mental health benefits, I tend to be a pretty anxious person by nature. So, I got into meditation and was enjoying the daily practice of observing my breath and eventually I wanted to go deeper with it, but I had this kind of aversion to religions. So at the start I avoided the Buddhist books, and I would only read the secular more contemporary books. Eventually I just started reading some of the Buddhist books and I realized really quickly that more than just soothing my anxiety; they dealt with real questions, like how to die peacefully and how to live a life with purpose. It went way deeper than my original meditation practice. So I ended up practicing with a local Zen Center for a bit, and I’ve practiced with a few other Sanghas through the years, more formally at times and less formally at other times, but I’ve continued to meditate almost every day since I started. It’s been a huge part of my life, I can’t imagine living without it now. Even when I am not as involved with a sangha, like at the moment, the philosophy guides me through, minute by minute.

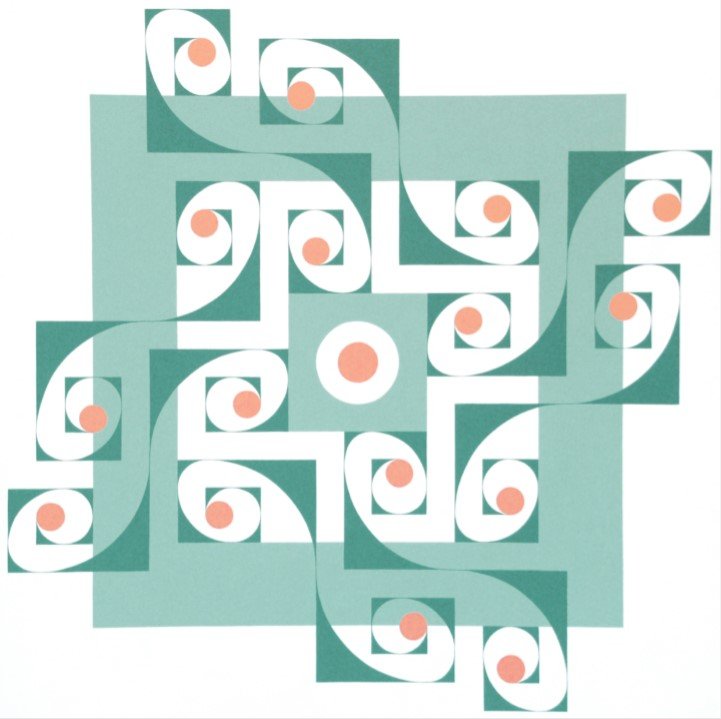

Dharma Wheel, ink on paper. Qwul’thilum (Dylan Thomas), 2016.

Image courtesy of the artist

I asked Dylan how his study and practice of Buddhism sits alongside his Indigenous identity. He responded:

In regards to the community’s reaction to my Buddhist practice, nobody seems very interested in it at all. So I’m glad that it doesn’t evoke a negative response, but I don’t think I’ve inspired anyone to investigate Eastern thought.

On a philosophical level, I found that Buddhist and Salish worldviews compliment each other. . . . For example, in Zen, they use the concept of “Shin,” and Salish culture has the concept of “skwalawyun.” These words both roughly translated to “heart-mind” in English. Because the heart (emotions) and mind (logic) are seen as distinct in contemporary Western culture, they don’t have a word that encompasses both. And when I began exploring Tibetan Buddhism, some of the parallels were stunning. For example, their masked dances were remarkably similar to the types of dances here on the coast. These are just a couple parallels I’ve found in my experience with Buddhism.

Another Vancouver-based artist, Tomoyo Ihaya, discussed how she came to the practice of Buddhism in relation to her art:

I grew up in Japan around conservative Buddhist grandparents who belonged to a very particular sect of Buddhism that was more concerned with formally following customs and rituals than it was concerned with the teachings. . . . So, I actually rejected Buddhism, and it was not until I went to university in Tokyo that I learned that Eastern philosophies talk about “emptiness” and “sense of order,” that I started becoming more curious about the actual teachings. When I came to Canada in 1994 . . . I met a soul sister, who is still a wonderful artist, and she directed me to Dharma talks and meditations, where I started inquiring inside myself. . . . This friend also introduced me to meditation, and that’s when I encountered the teachings of Buddhism that were rooted in a transient nature, in loving-kindness, and in beliefs of past and future lives. All of this opened me up to new ideas about how to live. And as it is in Tibetan Buddhism, or in my practice of Mahayana, this friend introduced me to a way of being personal in prayer, to always include the words, “May we get enlightened, for the sake of all other beings.” It’s not about one person’s refuge, but a way of thinking of every sentient being, because we are all interconnected.

So, this has really helped me to make art, not only philosophically, but also in terms of an attitude, because there’s lots of competition, ego, and self-expression in art, and I didn’t feel comfortable to push myself as an artist because this competition didn’t feel good. So making art, along with learning all of this, really helped me to keep my mind rather sane.

So there are a very diverse range of positions. Each artist is reflecting on what Buddhist studies scholars describe as modern Buddhism, considering Buddhism as a form of practice having relevance for issues in the contemporary world. And what I am exploring has to do with the cultural expressions of modern Buddhism, which is prevalent in Canada. But I’m not sure that Buddhism has had an impact in terms of shaping national culture.

Bodhi Tree, acrylic on canvas. Qwul’thilum (Dylan Thomas), 2016.

Image courtesy of the artist

That said, the Buddhist studies scholar Melissa Anne Marie Curley has discussed Canada’s artist-run culture in terms of Buddhist influences, describing some of its ideologies as “culturally Buddhist.” Curley refers to the work of artist collectives such as General Idea, Image Bank, and artists associated with Intermedia. Some members of these groups did in fact have Buddhist practices, although Curley’s essay does not necessarily get into that. However, she does refer to the influence of the French Fluxus artist Robert Filliou, who had a significant impact on the development of artist-run culture in Canada. In his artistic work, Filliou drew on the language of Zen, which has been widely commented upon, but he was a Dzogchen practitioner who found analogies between his practice of Buddhism and practice of art. He was interested in the analogy between art and Buddhist tantra. This wasn’t always explicit in the way that he talked about his artistic work, but a practitioner might recognize the correspondences, for example in his concept of the Eternal Network, which referred to a conceptual network of artists and creative practitioners as a means to activate a concept of inter-connection. The Eternal Network was an imaginative social architecture, a “mandala” we could say, in which each creative practitioner, absorbed in their own creative world, was concerned with processes of self and social transformation. The Eternal Network was as much real as it was illusory, as a “mind-object” perceptible through mind-transmission or telepathy, an analogy with the mind-direct practices of Dzogchen.

What Buddhism contributed to avant-garde forms of visual art practice was the possibility of an alternate social vision that recognized the potential of art and creativity as a means and an end in itself. This refers to the non-dualism of art and life, but also the non-dualism of art and society, even the non-duality of art and Buddhism. To generalize, I would say that for Canadian artists, as with artists around the world engaged with Buddhism, art and Buddhism coincide as forms of practice concerned with self- and social- transformation. Artists consider themselves as having a role to play in actualizing the creative potential of society, but also a role to play in creatively actualizing the potential of society. The conversation between Suzanne Lacy and Jodie Evans was very interesting as they have different but not entirely unrelated approaches to art, activism, and Buddhism, and I think this is in part to do with the US political context, where Buddhism has contributed to various forms of “disruptive” or “interruptive” protest towards issues such as race and civil rights, feminism, peace activism, and so on. This has a historical context related to the history and culture of protest in the US. But it is a little bit different in Canada, where this relationship between art, activism, and Buddhism tends to take a more personal form, as a kind of moral responsibility toward social change, so that personal change as expressed through art can be a catalyst for inter-personal change that may then impact on the social.

The conversation between Suzanne Lacy and Jodie Evans was very interesting as they have different but not entirely unrelated approaches to art, activism, and Buddhism, and I think this is in part to do with the US political context, where Buddhism has contributed to various forms of “disruptive” or “interruptive” protest towards issues such as race and civil rights, feminism, peace activism, and so on. This has a historical context related to the history and culture of protest in the US. But it is a little bit different in Canada, where this relationship between art, activism, and Buddhism tends to take a more personal form, as a kind of moral responsibility toward social change, so that personal change as expressed through art can be a catalyst for inter-personal change that may then impact on the social.

The Vancouver-based artist and educator Susan Stewart commented in relation to her own practice of art, activism and Buddhism:

When you start studying Dharma, in the beginning the whole first wheel of Dharma, the foundational teachings are about teaching you how to not cling to yourself and your ego. We cling with a tight fist, and one finger at a time they pry open, until our clinging lessens a little bit. You have to start with yourself in Buddhism. I did that for quite a long time and I was practicing and meditating on my own non-existence, on non-self, and the non-existence of my ego, and a contradiction starts popping up. How can I be happy when I’m empty, when I have no ego, when I have no self? Why would one make a truly existent artwork? There was a contradiction there because my understanding of art up until that point was that it was a “sign of self” at a certain point in your life. In my case I was an angry activist, so my signs were very political, but in my mind, they were still signs of myself.

I was having this contradictory experience of selflessness, egolessness, and emptiness, while dealing with art which was demanding presence, production, and action. During my foundational study of Buddhism, I couldn’t deal with the fact that art was always demanding something of me. Ten years later when I moved onto Mahayana, thankfully I got that far, this opened up a crack of emptiness. When you get to that space, if you open up a little bit of emptiness within yourself, what starts to happen is that you get more in touch with your heart again. . . . For the next 10 years I started making art that didn’t even look like art. I don’t think it was even readable to people, it was incoherent and illegible as art, but for me I was entering back into art and into social practice—a stream that was coming onto the scene as a discourse and with which I felt aligned. I started reading a lot of social practice material . . . identified with Fluxus, with happenings, and with performance art. Then for the next 10 years, I took on projects that were invisible, but to me they were art projects.

Activism can take the form of quiet, sometimes solitary, interventionist gestures regarding, for example, how one chooses to live one’s life against the grain of dominant social values as a practice of living. Or it can provide a counterpoint, as in the case of a social practice/installation work by Vancouver-based artist Lam Wong, who has created a work titled MA No.1 – The Space Between Objects Mu/Wu, which reconsiders the form and symbolism of traditional Chinese and Japanese tea ceremonies as social and performative intervention, as an antidote to the emotional and political charge of our time. In this case, the power of the work is in the artist’s capacity to situate or host a profound exchange between strangers in the midst of chaos, and for a moment to effect a moment of stillness, a glimpse of empty awareness.

Rose Mirror Mandala, Stathacos, Chrysanne. 2013. Photo by Matthias Herrmann

Rose Mirror Mandala, Stathacos, Chrysanne. 2013. Photo by Matthias Herrmann

The conversation between Suzanne Lacy and Jodie Evans was very interesting as they have different but not entirely unrelated approaches to art, activism, and Buddhism, and I think this is in part to do with the US political context, where Buddhism has contributed to various forms of “disruptive” or “interruptive” protest towards issues such as race and civil rights, feminism, peace activism, and so on. This has a historical context related to the history and culture of protest in the US. But it is a little bit different in Canada, where this relationship between art, activism, and Buddhism tends to take a more personal form, as a kind of moral responsibility toward social change, so that personal change as expressed through art can be a catalyst for inter-personal change that may then impact on the social.

The conversation between Suzanne Lacy and Jodie Evans was very interesting as they have different but not entirely unrelated approaches to art, activism, and Buddhism, and I think this is in part to do with the US political context, where Buddhism has contributed to various forms of “disruptive” or “interruptive” protest towards issues such as race and civil rights, feminism, peace activism, and so on. This has a historical context related to the history and culture of protest in the US. But it is a little bit different in Canada, where this relationship between art, activism, and Buddhism tends to take a more personal form, as a kind of moral responsibility toward social change, so that personal change as expressed through art can be a catalyst for inter-personal change that may then impact on the social.

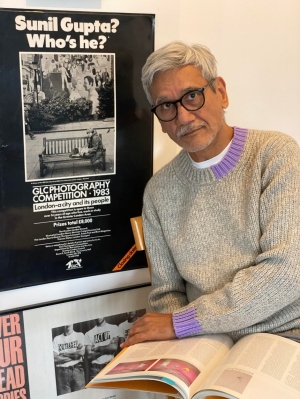

From Here to Eternity is the first major career retrospective of U.K.-based photographer Sunil Gupta, BComm 77.

From Here to Eternity is the first major career retrospective of U.K.-based photographer Sunil Gupta, BComm 77.